Summarized by Pat Rice, Historian

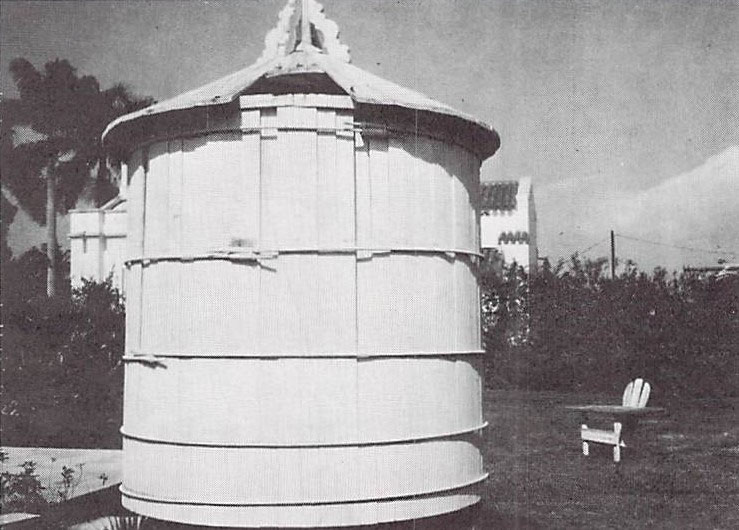

Imagine living here before 1966 and that your major source of water on Boca Grande was rainwater, collected in your privately-owned cistern during the rainy season for use during drier months. Sometimes there were droughts, necessitating strict water rationing. Or worse, unsanitary conditions because cisterns were open to the air, easily polluted by mosquitoes, insecticides, animals, and phosphate dust from island loading docks. Investigation by the Lee County Health Department had led to condemnation of tanks, and the alternative of surface water was deemed unfit to drink, with septic tanks polluting most of the island’s water supply. Residents began to sink well points to obtain a supply of water, but many found brown water filled with minerals, and others near the beach found only brackish water on their lots. Some residents defied the condemned water tanks and continued to use rainwater. Others purchased bottled water for drinking and cooking purposes, including Seaboard Coastline Railroad, who brought water in tank cars for personnel and to re-supply docked ships.

Over time, well points of good water went dry or began supplying brine. After storms, salt water encroachment became a major problem, with wells turning foul. And often, with weather-related power outages, residents no longer had generators for electric pumps to bring water into their homes. It was clear there was a need for an off-island water source, a water treatment plant, a pumping facility for a pipeline, storage, and an auxiliary on-island generator. All this required technical advice and significant capital investment. And most importantly, a coordinated effort on the part of residents, which had not happened before.

At that time, in November 1965, the Woman’s Club was the only organized club in existence capable of undertaking such a plan. Several members noted that Sanibel and Captiva Islands financed a water treatment system through an FHA loan, and decided to approach Seaboard Coastline Railroad for support.

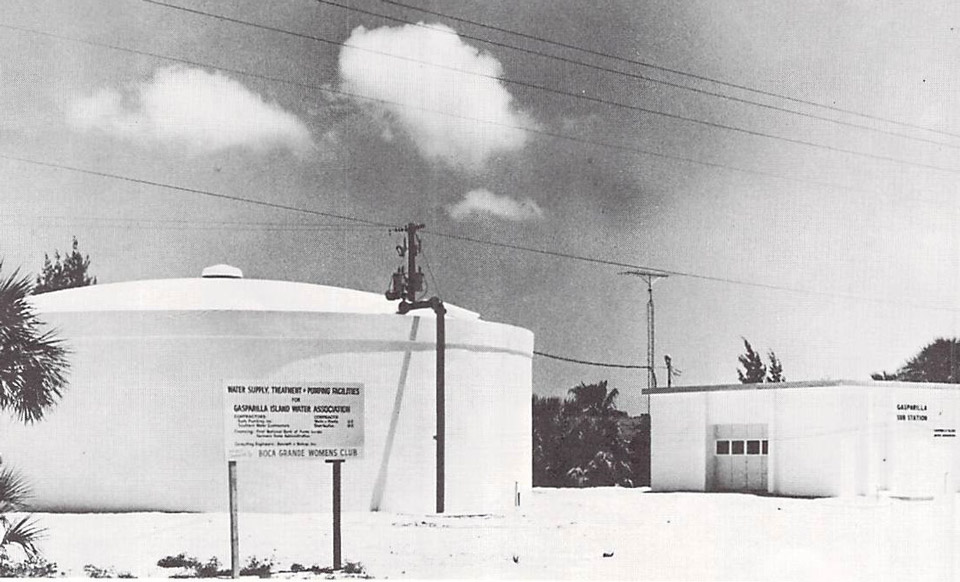

The company urged the Woman’s Club to proceed, and in February 1966, the Woman’s Club sponsored a discussion to pursue an FHA loan to finally acquire a good water supply. Through many months of meetings organized by the Woman’s Club and the development of a committee representing different island interests, the Gasparilla Island Water Association, GIWA, was created, with the Woman’s Club providing cohesion and eliciting support for the project.

It was a formidable task, given the conflicting facts, opinions and misinformation. The Woman’s Club carried out an effective educational program through a series of informational meetings to obtain necessary “subscribers” to sign up for the water ($60 per household).

Lealia Slotterbeck, President BGWC,1972-1975.

Catherine Gilbert, President BGWC, 1965-1968, 1969-1971.

Members went from person to person explaining the Water User’s Agreement and presenting facts and figures illustrating why the water was so necessary to the community…and why it would be an improvement, not a deterrent, to the island’s growth.

By the fall of 1967, the FHA loan application had been approved and a new water system was being completed. The water project won an award (one of the ten finalists out of 11,835 entries) in a national Women’s Club competition.

Not only was the goal of fresh water fully achieved, but increased community participation was met. Through the drive and leadership of The Woman’s Club, a significant community improvement was made by coordinating the participation of many residents, not just a few families. It was the culmination of many working together, and set the stage for heightened involvement on future initiatives.

(Participants included Miss Catherine Gilbert, Lealia Slotterbeck, Oberta Slotterbeck, Laura Sprague, Darrell Polk, Capt. Carey Johnson, Capt. Robert Johnson, Seaboard Coastline Railroad, and many others.)